Strange adventure

When Ludwig Leichhardt arrived in 1842, Australia had been thoroughly explored only along its southern fringes. There were no great river systems, as in North and South America, to lead explorers into the dry, harsh interior.

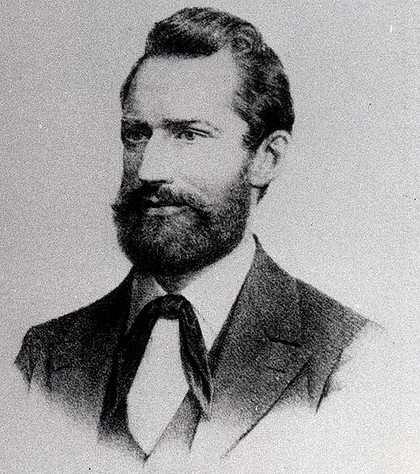

Few men were less prepared than Leichhardt to reconnoiter this wilderness. The dreamy son of a Prussian farmer, he had studied at the universities of Gottingen and Berlin, aiming to be a doctor. There is no record that he succeeded. In October 1840, he deserted from the army and fled to Sydney.

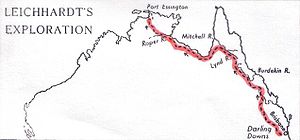

Leichhardt was known for his eccentric ways. He wore a Chinese coolie hat and carried a sword, because he was said to be terrified of firearms. His eyesight was as bad as his sense of direction. Nevertheless, he yearned to be the first to explore the land route from south to north along Australia’s Great Dividing Range from Sydney to Port Essington, a settlement near the continent’s northern tip.

He assembled a rag-tag crew and convinced well-to-do Australians to finance the trek. Ill-equipped, his troop of eight set off from the fertile region known as the Darling Downs in September 1844. Never straying more than ten miles from running water (they had not brought enough canteens), the group reached the eastern edge of the Gulf of Carpentaria in June 1845. There, naturalist John Gilbert was killed in an Aboriginal attack, and two other men were wounded. The surviving band traveled along the edge of the gulf and six months later stumbled into Port Essington. They returned by sea to Sydney, where they had been given up for dead.

The expedition made Leichhardt the most famous man in Australia. Citizens took up collections for him, and foreign geographical societies bestowed medals. The king of Prussia pardoned him for desertion. All of that stimulated Leichhardt to plan an even more spectacular journey.

This time he would start once more from the Darling Downs, head north again for Carpentaria, then strike west all the way across the continent. His route would take him through hostile tribal lands, and across some of the world’s most forbidding deserts. Once again, he recruited a group of eight followers and convinced backers to provide him with supplies. Carrying two years’ supplies and accompanied by a herd of sheep, goats, and cattle, he set out in December 1846, the hottest time of year. Eight months later, he was back. His party had wandered aimlessly and lost their livestock. According to one account, Leichhardt had given strange commands, telling his followers, for example, to cook game with the entrails left in, which led to bouts of sickness. When his own supplies ran low, he filched from others. Eventually, they gave up in disgust and despair. Despite this fiasco, Leichhardt was able to find backers for another expedition. In April 1848, he set forth with six mates, fifty head of cattle, twenty mules, and seven horses. Somewhere on their journey, the entire party, man and beast, disappeared without a trace.

Rumors about Leichhardt’s fate continued to crop up for years. It was said that he had been killed by Aborigines or drowned in flash floods. There were tales of a wild white man in the bush, living with natives, possibly a survivor of the lost expedition. At least two of Leichhardt’s camps were discovered, and at various places in the interior, trees were found marked with a mysterious L. In 1880, the Sydney Bulletin coined the term Franklin of Australian exploration, ranked Leichhardt’s final foray with Sir John Franklin’s ill-fated arctic probe.

Leichhardt himself had long since been embedded in official Australian lore. Plaques marked various sites along his first expeditionary trail. In the state of Queensland, where most of his early exploring took place, a mountain range and a river were named after him. In Sydney, a suburb earned the same distinction, and his surname identifies twenty varieties of Australian plants.

Mysterious Expedition

In 1938, an expedition headed by the president of the Royal Geographic Society of South Australia went to the edge of the Simpson Desert, deep in the center of the country, drawn by rumors that seven or eight skeletons were lying there. The party found only unidentifiable fragment of bone and teeth, and two coins – a half sovereign and a Maundy three-pence, both minted before the doomed expedition left Sydney.